GMO labeling now hidden in plain sight

Why are genetically modified organisms (GMO) now linked to the National Sea Grant College Program Act, a 50-year-old piece of legislation that has nothing to do with farming or the U.S. Department of Agriculture? Welcome to politics and the big-dollar influence of lobbyists …

The National Sea Grant College Program Act was instituted in 1966. It is a network of 33 Sea Grant Colleges and universities for scientific research, education, training, and extension projects for the conservation and practical use of the coasts, Great Lakes, and other marine areas.

The National Sea Grant College Program Act falls under the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) within the U.S. Department of Commerce.

GMOs, basically, are any organisms whose genetic material has been altered using genetic engineering. In 1982, the FDA approved the first GMO — Humulin, insulin produced by genetically engineered E. coli bacteria. The first GMO on grocery shelves came in 1994 when the FDA green-lighted the Flavr Savr tomato; the delayed-ripening tomato had a longer shelf life than conventional tomatoes. However, the Flavr Savr tomatoes were discontinued in 1997.

Interestingly, in 1996 Monsanto acquired Agracetus, which held a majority interest in Calgene, creators of the Flavr Savr GMO fruit (or vegetable, depending on how you choose to slice it). In '97, Monsanto purchased the remaining shares of Calgene.

According to the Non-GMO Project, more than 80 percent of all GMOs are engineered for herbicide tolerance. GMOs are a direct extension of chemical agriculture and are developed and sold by the world's biggest chemical companies, like Monsanto.

OK, now that you have a little background: How do GMOs fit into the long-standing National Sea Grant College Program Act?

S. 764: ‘and for other purposes'

On March 17, 2015, U.S. Sen. Roger Wicker (R-Miss.) introduced S. 764 — ostensibly “a bill to reauthorize and amend the National Sea Grant College Program Act, and for other purposes.”

It makes sense that Wicker would be involved; four universities in his home state — Jackson State University, Mississippi State University, the University of Mississippi, and the University of Southern Mississippi — are part of the Mississippi-Alabama Sea Grant Consortium.

“It is my hope that food corporations reject high-tech gimmicks, like QR codes, and stick with the simple, non-judgmental disclosures we have already seen popping up on shelves across the country.”

Gary Hirshberg

Just Label It

On July 6, 2016, the U.S. Senate approved the bill. On July 14, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a bill to amend the Agricultural Marketing Act of 1946, now requiring food labels to disclose if the food contains GMO ingredients.

On July 29, President Obama signed into law S. 764 (also called the DARK Act by opponents), which also directs the Secretary of Agriculture to come up with within the next 30 months a national labeling standard regarding GMOs.

That’s a win for consumers — correct? You may think that, but there's more to the story. And, you’re probably still curious about how GMOs fit into the National Sea Grant College Program Act. Look no further than “and for other purposes” for things to get interesting …

From Chris Morran at Consumerist:

S. 764 began life as “A bill to reauthorize and amend the National Sea Grant College Program Act” and still technically carries that name.

That original bill, which had nothing to do with food labeling, was initially passed by the Senate, but since it never made it any further, Sen. [Mitch] McConnell was able to use the husk of the Sea Grant College bill as a way to expedite later bills he felt deserved to be on the fast track.

First, he hollowed out S. 764 and replaced it with a bill to defund Planned Parenthood. Then that text was gutted and replaced with the first attempt at outlawing state-level GMO labeling laws by creating a voluntary national labeling standard.

When that bill failed — and with the July 1 launch of the Vermont labels approaching — two of the Senate’s biggest recipients of agribusiness money, Sen. Pat Roberts (R-Kan.) and Sen. Debbie Stabenow (D-Mich.) rushed out a “compromise” bill that would eventually create a national standard while outlawing any state-level labeling rules (unless they agree exactly with the national standard, which would make them redundant anyway).

Because McConnell fast-tracked that bill, it never saw a day in committee, where there would have been hearings involving stakeholders, followed by proposed amendments. Instead, it went straight to the Senate floor, where members from both sides of the political spectrum okayed it with minimal consideration.

- More: Pat Roberts' top contributors

- More: Debbie Stabenow's top contributors

- Also: What is “fast track” for a bill?

GMO labeling law falls short

Stabenow, the ranking member of the Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition and Forestry, said the bipartisan bill was “a win for consumers and families. For the first time ever, consumers will have a national, mandatory label for food products that contain genetically modified ingredients.

“Throughout this process, I worked to ensure that any agreement would recognize the scientific consensus that biotechnology is safe, while also making sure consumers have the right to know what is in their food. I also wanted a bill that prevents a confusing patchwork of 50 different rules in each state. This bill achieved all of those goals, and most importantly recognizes that consumers want more information about the foods they buy.”

In the wake of S. 764, should we be concerned about the foods we eat? It’s a straightforward question — but much like the path to law for S. 764, there is not a straightforward answer.

There were 261 people from 97 organizations that lobbied on behalf of S. 764, including Unilever and Kellogg’s, among others, that are part of Monsanto.

There were 411 people from 121 organizations that lobbied on behalf of H.R. 1599, the Safe and Accurate Food Labeling Act of 2015, including former Arkansas representative and senator Blanche Lincoln.

(As noted by Newsmax, Lincoln has good reason to lobby on behalf of Monsanto. According to the Farm Bureau, agriculture is the top industry in Arkansas, pumping around $16 billion into the state's economy annually.)

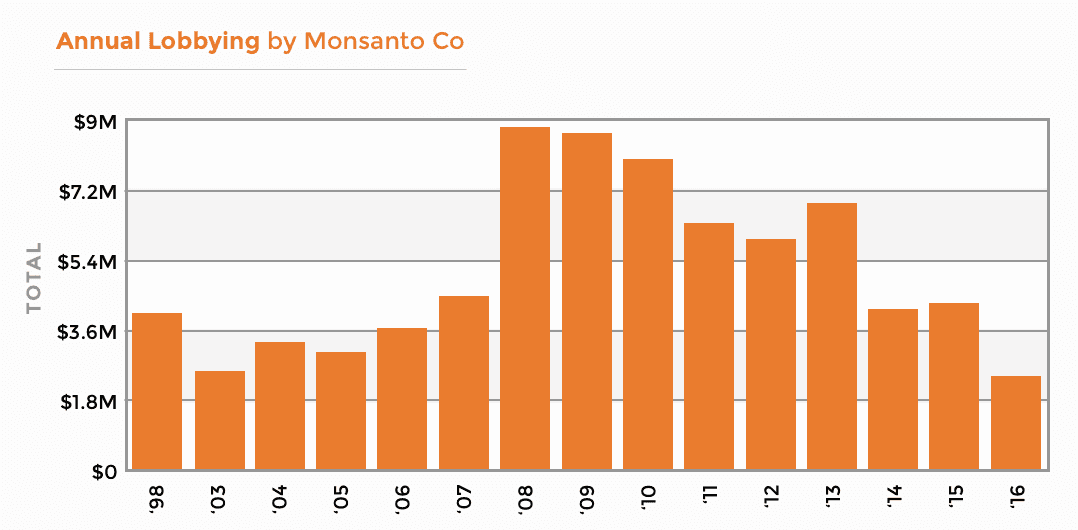

Through Labor Day weekend, Monsanto had 24 lobbyists on record in 2016 and had totaled $2,450,000 in lobbying expenditures. Last year, Monsanto spent $4,330,000.

Despite Stabenow’s claim to “making sure consumers have the right to know what is in their food,” others believe the law leaves a lot to be desired.

Ronnie Cummins, international director of the Organic Consumers Association, said the bill “trampled on consumer and states’ rights, choosing instead [to] serve the interests of Monsanto and the Grocery Manufacturers Association.”

Indeed, the Grocery Manufacturers Association has a history of opposing transparency on behalf of consumers:

- 1993-94 — Opposed labels on dairy products derived from cows injected with Monsanto’s controversial Bovine Growth Hormone (rBGH).

- 1998 — Supported, along with Monsanto, the use of GMO seeds, food irradiation, and sewage sludge in organic agriculture, spawning a nationwide organic consumer backlash.

- 2001 — Along with the chocolate industry, lobbied against legislation in the U.S. Congress that would have exposed slave-like child labor practices on cacao plantations in Africa.

- 2004 — Helped defeat a California bill that would have set nutrition standards for school food.

S. 764 allows companies several ways to disclose the use of GMOs: a QR code, an 800 number, or a website on the packaging — but no further information on the label itself is required.

“In the wake of the creation of a national, mandatory labeling system, Campbell’s, Mars, and Dannon have already publicly committed to keeping this simple disclosure on their packages as USDA sorts out the rules for implementation of this new law,” said Gary Hirshberg, chairman of the Just Label It campaign.

“In recent months, we have seen real-world examples of how clear, on-package labeling can work for both consumers and industry,” Hirshberg added. “It is my hope that food corporations reject high-tech gimmicks, like QR codes, and stick with the simple, non-judgmental disclosures we have already seen popping up on shelves across the country.”