Ginger is an important part of fighting cancer

We all know about and have eaten some ginger during our lifetimes. It’s a sweet, aromatic root with a pungent and hot taste. Some people enjoy drinking it as a tea, some eat it with sushi, and others enjoy it as candy. Ginger the rhizome (otherwise known as the underground stem of the plant Zingiber officinale) is a common food ingredient that has been used for thousands of years in Ayurvedic and traditional Chinese medicineA medical system that has been used for thousands of years to prevent, diagnose, and treat disease. Also called Oriental medicine and TCM, it includes acupuncture, diet, herbal therapy, meditation, physical exercise, and massage. to treat a wide variety of conditions.

Practitioners most commonly use ginger to treat conditions related to digestion: nausea, vomiting, upset stomach, diarrhea, and motion sickness. To this day, many people grow up sipping ginger ale when sick with a stomach bug. Clinical studies have shown ginger to be helpful for nausea during pregnancy, and it is one of the safest natural therapies for this type of condition. In fact, it is the only natural product — which is actually a food — that even conventional medicine recommends and has given an “approved use” stamp for nausea in pregnancy, as all other medications have side effects that are harmful to mother and baby.

Ginger contains nutrients that have good spasmolytic properties, which is just a way to say that ginger micronutrients soothe and relax the intestines. Doctors commonly recommend ginger to patients who have undergone intestinal surgery, as it also confers great protection against infections. Ginger helps aid many anti-inflammatory problems that occur in smooth muscles or even in the skeletal muscles.

People use ginger not only for GI troubles but also for arthritis, the common cold and flu, painful menstruation symptoms, headaches, and even various cancers. As of the writing of this book, there are more than 2,400 studies on the various benefits of ginger published in the scientific literature.

Ginger: Activities and Actions

Ginger has been shown to have the following properties: [1]

- Immunomodulatory (strengthens the immune system)

- Antitumorigenic (prevents tumors development)

- Anti-inflammatory

- Antiarthritic

- Antihyperglycemic (prevents elevated blood glucose)

- Antihyperlipidemic (prevents elevated blood lipids)

- Antiemetic actions (prevents nausea and vomiting)

- Chemopreventive actions (helps prevent cancer growth when consumed frequently)

Some of the most studied actions of ginger are its analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects through the inhibition of NF-kB, COX-2, and 5-LOX (the major pathways and switches of inflammation mentioned previously). Ginger also has been shown to protect against cancers and to demonstrate a chemoprotective effect, meaning it protects the body from the side effects of chemotherapy. Some characteristics of ginger’s actions include the following: [2]

- Induction of apoptosisA type of cell death in which a series of molecular steps in a cell lead to its death. This is one method the body uses to get rid of unneeded or abnormal cells. The process of apoptosis may be blocked in cancer cells. Also called programmed cell death. (programmed cell death) of cancer cells

- Inhibits IkBa kinase activation (upregulates apoptosis)

- Upregulation of BAX (a proapoptosis gene)

- Downregulation of Bcl-2 proteins (cancer associated)

- Downregulation of prosurvival genes (anti-apoptotic) Bcl-xl, Mcl-1, and Survivin

- Downregulation of cell-cycle-regulating proteins, including cyclin D1 and cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (CDK4) (cancer associated)

- Increased expression of CDK inhibitor, p21 (anticancer associated)

- Inhibition of c-Myc, hTERT (cancer associated)

- Abolishes RANKL-induced NF-kB activation

- Inhibits osteoclastogenesis (type of bone cell that breaks down bone tissue to remodel and repair)

- Suppresses human breast-cancer-induced bone loss

If you or a loved one has been stricken with cancer, then you probably know the importance of all of these functions. Thus, it’s easy to see that ginger can play an important role in regulating not only inflammation but also various signals that affect cancer cells.

Ginger and its constituents have been shown to inhibit the following cancers: [3]

- Breast cancer

- Colon and rectal cancer

- Leukemia

- Liver cancer

- Lung cancer

- Melanoma

- Pancreatic cancer

- Prostate cancer

- Skin cancer

- Stomach cancer

To demonstrate just how important ginger can be to helping eliminate cancers, let’s look at one example: ovarian cancer.

In ovarian cancer, there are usually some indicators of the inflammation, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), interleukin-8, and prostaglandin E2 (PEG2). Ginger extracts have been shown to greatly decrease these inflammatory markers in ovarian cancer patients. [4] Thus not only can it be taken as a tea or food to help warm someone who may feel cold or have nausea (especially those being treated with chemotherapy), but ginger also has a beneficial effect for those with serious health conditions like ovarian cancer.

Another interesting aspect of ginger is its hypoglycemic effect against enzymes linked to type 2 diabetes. Anyone who has diabetes or even mild insulin resistance can enjoy this added benefit of ginger; it is not harmful to those who are taking diabetes medication. Instead, it may improve overall glucose control. In addition, keeping blood glucose in the lower/normal range is optimal for those with cancer, even if they do not have diabetes.

To sum up, ginger is a strong antioxidant that can help with metabolic syndrome, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, dementia, and inflammatory conditions such as arthritis, osteoporosis, and even cancers. Thus, in addition to taking Bosmeric-SR, one should try to include organic ginger in the diet as much as possible. Try adding it to foods like salsa, smoothies, or stir-fry. Ginger is a staple in most Thai and Indian curries and sauces, which are both fun and easy to make at home to liven up the flavors of any meal. You can also cut off half an inch of organic ginger root and blend it in a juicer along with other veggies and fruits to give your juice a kick of spiciness. For those with weak digestion, see Ginger Elixir Recipe to jump-start your digestive system before meals.

Which ginger supplement is best for me?

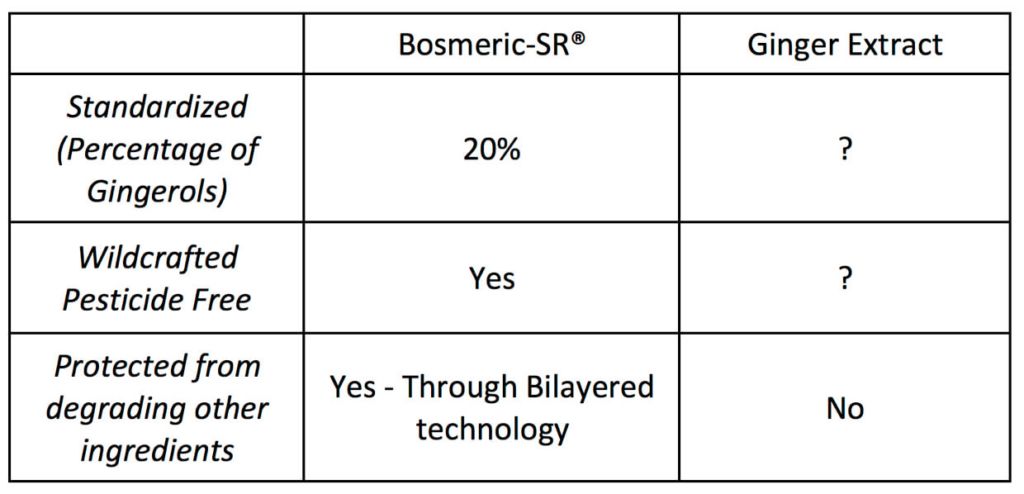

Research shows that gingerols are some of the most important bioactive anti-inflammatory components in ginger. Most people have taken ginger products, but they may have experienced limited benefits because the supplement contained plain ginger powder. Most dietary supplements on the market contain ginger powder, which is virtually devoid of the beneficial compounds found naturally in ginger.

The ginger extract should be standardized to contain from 10 percent to 20 percent gingerols; the higher the percentage of gingerols, the stronger the health benefits (and the more pungent it is). Bosmeric-SR contains the highest amount of gingerols available today, standardized at 20 percent. A product that says it contains “ginger powder” or “ginger root” and that is not standardized to have gingerols in it truly is not worth taking. You are much better off buying organic ginger root and consuming it as a food, making it into a tea or using some of it in your cooking.

If you take a ginger dietary supplement, make sure it has at least 10 percent standardized gingerols and take 100 mg twice daily with food (most products recommend taking ginger with food). Bosmeric-SR gives you 200 mg of 20 percent gingerols twice daily, with a sustained release that offers lasting effects over eight hours — virtually your entire working day.

Since all four clinically tested and patented ingredients (Curcumin C3 Complex, Boswellin PS, Ginger [gingerols 20 percent ], Bioperine) in Bosmeric-SR act upon cancer pathways,[v] the formulation may help those who have cancer. Its anti-inflammatory and stomach-calming effects are wonderful for those undergoing chemotherapy, as nausea is a common side effect. Taking Bosmeric-SR may not only reduce feelings of nausea safely but also help the condition and protect the non-cancerous cells at the same time. For everyone else, Bosmeric-SR may be a wonderful way to help reduce systemic inflammation in the body and prevent future chronic diseases and cancers from occurring in the first place.

For more detailed information on 10 steps to optimum health using diet and lifestyle changes and the use of natural anti-inflammatories, please read An Inflammation Nation.

Modified by permission from An Inflammation Nation by Sunil Pai © 2015.

References

- Mahima et al., “Immunomodulatory and Therapeutic Potentials of Herbal, Traditional/Indigenous and Ethnoveterinary Medicines,” Pak J Biol Sci 15, no. 16 (2012): 754–74; D Tejasari, “Evaluation of Ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe) Bioactive Compounds in Increasing the Ratio of T-cell Surface Molecules of CD3+CD4+:CD3+CD8+ In-Vitro,” Malays J Nutr 13, no. 2 (2007): 161–70; Y Takada, A Murakami, and B B Aggarwal, “Zerumbone Abolishes NF-kappaB and IkappaBalpha Kinase Activation Leading to Suppression of Antiapoptotic and Metastatic Gene Expression, Upregulation of Apoptosis, and Downregulation of Invasion,” Oncogene 24, no. 46 (2005): 6957–69; B Sung et al., “Zerumbone Abolishes RANKL-Induced NF-kappaB Activation, Inhibits Osteoclastogenesis, and Suppresses Human Breast Cancer-Induced Bone Loss in Athymic Nude Mice,” Cancer Res 69 no. 4 (2009): 1477–84; S N Omoregie et al., “Antiproliferative Activities of Lesser Galangal (Alpinia officinarum Hance Jam1), Turmeric (Curcuma longa L.), and Ginger (Zingiber officinale Rosc.) against Acute Monocytic Leukemia,” J Med Food 1, no. 7 (2013): 647–55; K Tsuboi et al., “Zerumbone Inhibits Tumor Angiogenesis via NF-κB in Gastric Cancer,” Oncol Rep 31, no. 1 (2014): 57–64; Q Liu et al., “6-Shogaol Induces Apoptosis in Human Leukemia Cells through a Process Involving Caspase-mediated Cleavage of eIF2α,” Mol Cancer 12, no. 1 (2013): 135; M Brahmbhatt et al., “Ginger Phytochemicals Exhibit Synergy to Inhibit Prostate Cancer Cell Proliferation,” Nutr Cancer 65, no. 2 (2013): 263–72; A Al-Nahain, R Jahan, and M Rahmatullah, “Zingiber Officinale: A Potential Plant against Rheumatoid Arthritis,” Arthritis (2014): 159089; A Chopra et al., “Ayurvedic Medicine Offers a Good Alternative to Glucosamine and Celecoxib in the Treatment of Symptomatic Knee Osteoarthritis: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Controlled Equivalence Drug Trial,” Rheumatology 52, no. 8 (2013): 1408–17; T Arablou et al., “The Effect of Ginger Consumption on Glycemic Status, Lipid Profile and Some Inflammatory Markers in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus,” Int J Food Sci Nutr 65, no. 4 (2014): 515–20; R Haniadka et al., “A Review of the Gastroprotective Effects of Ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe),” Food Funct 4, no. 6 (2013): 845–55; A R Khuda-Bukhsh, S Das, and S K Saha, “Molecular Approaches toward Targeted Cancer Prevention with Some Food Plants and Their Products: Inflammatory and other Signal Pathways,” Nutr Cancer 66, no. 2 (2014): 194–205; P L Palatty et al., “Ginger in the Prevention of Nausea and Vomiting: A review,” Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr, 53, no. 7 (2013): 659–69; J L Ryan et al., “Ginger (Zingiber officinale) Reduces Acute Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea: A URCC CCOP Study of 576 Patients,” Support Care Cancer 20, no. 7 (July 2012): 1479–89; F Dabaghzadeh, H Khalili, and S Dashti-Khavidaki, “Ginger for Prevention or Treatment of Drug-Induced Nausea and Vomiting,” Curr Clin Pharmacol (2013); M R Cominetti et al., “[6]-Gingerol as a Cancer Chemopreventive Agent: A Review of Its Activity on Different Steps of the Metastatic Process,” Mini Rev Med Chem 14, no. 4 (2014): 313–21; F Mohammadi et al., “Protective Effect of Zingiber Officinale Extract on Rat Testis after Cyclophosphamide Treatment,” Andrologia 46, no. 6 (2014): 680–6; A Angelini et al., “Modulation of Multidrug Resistance P-glycoprotein Activity by Antiemetic Compounds in Human Doxorubicin-Resistant Sarcoma Cells (MES-SA/Dx-5): Implications on Cancer Therapy,” J Biol Regul Homeost Agents 27, no. 4 (2013): 1029–37; M M Taha et al., “Potential Chemoprevention of Diethylnitrosamine-Initiated and 2-Acetylaminofluorene-Promoted Hepatocarcinogenesis by Zerumbone from the Rhizomes of the Subtropical Ginger (Zingiber zerumbet),” Chem Biol Interact 186, no. 3 (Aug. 5, 2010): 295–305; A A Oyagbemi, A B Saba, and O I Azeez, “Molecular Targets of [6]-Gingerol: Its Potential Roles in Cancer Chemoprevention,” Biofactors 36, no. 3 (2010): 169–78.

- Mahima et al., “Immunomodulatory and Therapeutic Potentials of Herbal, Traditional/Indigenous and Ethnoveterinary Medicines,” Pak J Biol Sci 15, no. 16 (2012): 754–74; D Tejasari, “Evaluation of Ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe) Bioactive Compounds in Increasing the Ratio of T-cell Surface Molecules of CD3+CD4+:D3+CD8+ In-Vitro,” Malays J Nutr 13, no. 2 (2007): 161–70; Y Takada, A Murakami, B B Aggarwal, “Zerumbone Abolishes NF-kappaB and IkappaBalpha Kinase Activation Leading to Suppression of Antiapoptotic and Metastatic Gene Expression, Upregulation of Apoptosis, and Downregulation of Invasion,” Oncogene 24, no. 46 (2005): 6957–69; B Sung et al., “Zerumbone Abolishes RANKL-Induced NF-kappaB Activation, Inhibits Osteoclastogenesis, and Suppresses Human Breast Cancer-Induced Bone Loss in Athymic Nude Mice,” Cancer Res 69, no. 4 (2009): 1477–84; S N Omoregie et al., “Antiproliferative Activities of Lesser Galangal (Alpinia officinarum Hance Jam1), Turmeric (Curcuma longa L.), and Ginger (Zingiber officinale Rosc.) against Acute Monocytic Leukemia,” J Med Food 16, no. 7 (2013): 647–55; K Tsuboi et al., “Zerumbone Inhibits Tumor Angiogenesis via NF-κB in Gastric Cancer,” Oncol Rep 31, no. 1 (2014): 57–64; Q Liu et al., “6-Shogaol Induces Apoptosis in Human Leukemia Cells through a Process Involving Caspase-Mediated Cleavage of eIF2α,” Mol Cancer 12, no. 1 (Nov. 12, 2013): 135; M Brahmbhatt et al., “Ginger Phytochemicals Exhibit Synergy to Inhibit Prostate Cancer Cell Proliferation,” Nutr Cancer 65, no. 2 (2013): 263–72; A Al-Nahain, R Jahan, and M Rahmatullah, “Zingiber Officinale: A Potential Plant against Rheumatoid Arthritis,” Arthritis (2014): 159089; A Chopra et al., “Ayurvedic Medicine Offers a Good Alternative to Glucosamine and Celecoxib in the Treatment of Symptomatic Knee Osteoarthritis: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Controlled Equivalence Drug Trial,” Rheumatology 52, no. 8 (2013): 1408–17; T Arablou et al., “The Effect of Ginger Consumption on Glycemic Status, Lipid Profile and Some Inflammatory Markers in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus,” Int J Food Sci Nutr 65, no. 4 (June 2014): 515–20; R Haniadka et al., “A Review of the Gastroprotective Effects of Ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe),” Food Funct 4, no. 6 (2013): 845–55; A R Khuda-Bukhsh, S Das, and S K Saha, “Molecular Approaches toward Targeted Cancer Prevention with Some Food Plants and Their Products: Inflammatory and Other Signal Pathways,” Nutr Cancer 66, no. 2 (2014): 194–205; P L Palatty et al., “Ginger in the Prevention of Nausea and Vomiting: A Review,” Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 53, no. 7 (2013): 659–69; J L Ryan et al., “Ginger (Zingiber officinale) Reduces Acute Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea: A URCC CCOP Study of 576 Patients,” Support Care Cancer 20, no. 7 (July 2012): 1479–89; F Dabaghzadeh, H Khalili, and S Dashti-Khavidaki, “Ginger for Prevention or Treatment of Drug-Induced Nausea and Vomiting,” Curr Clin Pharmacol (Nov. 11, 2013); M R Cominetti et al., “[6]-Gingerol as a Cancer Chemopreventive Agent: A Review of Its Activity on Different Steps of the Metastatic Process,” Mini Rev Med Chem 14, no. 4 (2014): 313–21; F Mohammadi et al., “Protective Effect of Zingiber Officinale Extract on Rat Testis after Cyclophosphamide Treatment,” Andrologia 46, no. 6 (2014): 680–6; A Angelini et al., “Modulation of Multidrug Resistance P-glycoprotein Activity by Antiemetic Compounds in Human Doxorubicin-Resistant Sarcoma Cells (MES-SA/Dx-5): Implications on Cancer Therapy,” J Biol Regul Homeost Agents 27, no. 4 (2013): 1029–37; M M Taha et al., “Potential Chemoprevention of Diethylnitrosamine-Initiated and 2-Acetylaminofluorene-Promoted Hepatocarcinogenesis by Zerumbone from the Rhizomes of the Subtropical Ginger (Zingiber zerumbet),” Chem Biol Interact 163, no. 3 (2010): 295–305; A A Oyagbemi, AB Saba, and O I Azeez, “Molecular Targets of [6]-gingerol: Its Potential Roles in Cancer Chemoprevention,” Biofactors 36, no. 3 (2010): 169–78.

- Mahima et al., “Immunomodulatory and Therapeutic Potentials of Herbal, Traditional/Indigenous and Ethnoveterinary Medicines,” Pak J Biol Sci 15, no. 16 (2012): 754–74; D Tejasari, “Evaluation of Ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe) Bioactive Compounds in Increasing the Ratio of T-cell Surface Molecules of CD3+CD4+:CD3+CD8+ In-Vitro,” Malays J Nutr 13, no. 2 (2007): 161–70; Y Takada, A Murakami, and B B Aggarwal, “Zerumbone Abolishes NF-kappaB and IkappaBalpha Kinase Activation Leading to Suppression of Antiapoptotic and Metastatic Gene Expression, Upregulation of Apoptosis, and Downregulation of Invasion,” Oncogene 24, no. 46 (2005): 6957–69; B Sung et al., “Zerumbone Abolishes RANKL-Induced NF-kappaB Activation, Inhibits Osteoclastogenesis, and Suppresses Human Breast Cancer-Induced Bone Loss in Athymic Nude Mice,” Cancer Res 69, no. 4 (2009): 1477–84; S N Omoregie et al., “Antiproliferative Activities of Lesser Galangal (Alpinia officinarum Hance Jam1), Turmeric (Curcuma longa L.), and Ginger (Zingiber officinale Rosc.) against Acute Monocytic Leukemia,” J Med Food 16, no. 7 (2013): 647–55; K Tsuboi et al., “Zerumbone Inhibits Tumor Angiogenesis via NF-κB in Gastric Cancer,” Oncol Rep 31, no. 1 (2014): 57–64; Q Liu et al., “6-Shogaol Induces Apoptosis in Human Leukemia Cells through a Process Involving Caspase-Mediated Cleavage of eIF2α,” Mol Cancer 12, no. 1 (2013): 135; M Brahmbhatt et al., “Ginger Phytochemicals Exhibit Synergy to Inhibit Prostate Cancer Cell Proliferation,” Nutr Cancer 65, no. 2 (2013): 263–72; A Al-Nahain, R Jahan, and M Rahmatullah, “Zingiber officinale: A Potential Plant against Rheumatoid Arthritis,” Arthritis (2014): 159089; A Chopra et al., “Ayurvedic Medicine Offers a Good Alternative to Glucosamine and Celecoxib in the Treatment of Symptomatic Knee Osteoarthritis: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Controlled Equivalence Drug Trial,” Rheumatology 52, no. 8 (2013): 1408–17; T Arablou et al., “The Effect of Ginger Consumption on Glycemic Status, Lipid Profile and Some Inflammatory Markers in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus,” Int J Food Sci Nutr 65, no. 4 (2014): 515–20; R Haniadka et al., “A Review of the Gastroprotective Effects of Ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe),” Food Funct 4, no. 6 (2013): 845–55; A R Khuda-Bukhsh, S Das, and S K Saha, “Molecular Approaches toward Targeted Cancer Prevention with Some Food Plants and Their Products: Inflammatory and other Signal Pathways,” Nutr Cancer 66, no. 2 (2014): 194–205; P L Palatty et al., “Ginger in the Prevention of Nausea and Vomiting: A Review,” Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 53, no. 7 (2013): 659–69; J L Ryan et al., “Ginger (Zingiber officinale) Reduces Acute Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea: A URCC CCOP Study of 576 Patients,” Support Care Cancer 20, no. 7 (2012): 1479–89; F Dabaghzadeh, H Khalili, and S Dashti-Khavidaki, “Ginger for Prevention or Treatment of Drug-Induced Nausea and Vomiting,” Curr Clin Pharmacol (Nov. 11, 2013); M R Cominetti et al., “[6]-gingerol as a Cancer Chemopreventive Agent: A Review of Its Activity on Different Steps of the Metastatic Process,” Mini Rev Med Chem 14, no. 4 (2014): 313–21; F Mohammadi et al., “Protective Effect of Zingiber officinale Extract on Rat Testis after Cyclophosphamide Treatment,” Andrologia 46, no. 6 (2014): 680–6; A Angelini et al., “Modulation of Multidrug Resistance P-glycoprotein Activity by Antiemetic Compounds in Human Doxorubicin-Resistant Sarcoma Cells (MES-SA/Dx-5): Implications on Cancer Therapy,” J Biol Regul Homeost Agents 27, no. 4 (2013): 1029–37; M M Taha et al., “Potential Chemoprevention of Diethylnitrosamine-Initiated and 2-Acetylaminofluorene-Promoted Hepatocarcinogenesis by Zerumbone from the Rhizomes of the Subtropical Ginger (Zingiber zerumbet),” Chem Biol Interact 163, no. 3 (2010): 295–305; A A Oyagbemi, A B Saba, and O I Azeez, “Molecular Targets of [6]-gingerol: Its Potential Roles in Cancer Chemoprevention,” Biofactors 36, no. 3 (2010): 169–78.

- J Rhode, S Fogoros, and S Zick, “Ginger Inhibits Cell Growth and Modulates Angiogenic Factors in Ovarian Cancer Cells,” BMC Complement Altern Med 7 (2007): 44.

- B Sung et al., “Cancer Cell Signaling Pathways Targeted by Spice-Derived Nutraceuticals,” Nutr Cancer 64, no. 2 (2012): 173–97; S C Gupta et al., “Regulation of Survival, Proliferation, Invasion, Angiogenesis, and Metastasis of Tumor Cells through Modulation of Inflammatory Pathways by Nutraceuticals,” Cancer Metastasis Rev 29, no. 3 (2010): 405–34; B B Aggarwal et al., “Molecular Targets of Nutraceuticals Derived from Dietary Spices: Potential Role in Suppression of Inflammation and Tumorigenesis,” Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 234, no. 8 (2009): 825–49.