The ‘deregulated status’ of GMOs

Genetically modified organism, it sounds like something from a sci-fi movie. However, genetic modification affects many of the products we consume on a daily basis. The Center for Food Safety estimates up to 92 percent of U.S. corn is genetically engineered, as are 94 percent of soybeans, and 94 percent of cotton (cottonseed oil is often used in food products). It has been estimated that upwards of 75 percent of processed foods on supermarket shelves contain genetically engineered ingredients.

According to the International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-biotech Applications (ISAAA), 2015 marked the 20th year of the commercialization of biotech crops. An unprecedented cumulative hectarage of 2 billion hectares of biotech crops — equivalent to twice the total land mass of the U.S. (937 million hectares) — were cultivated globally in up to 28 countries annually, in the 20-year period 1996 to 2015.

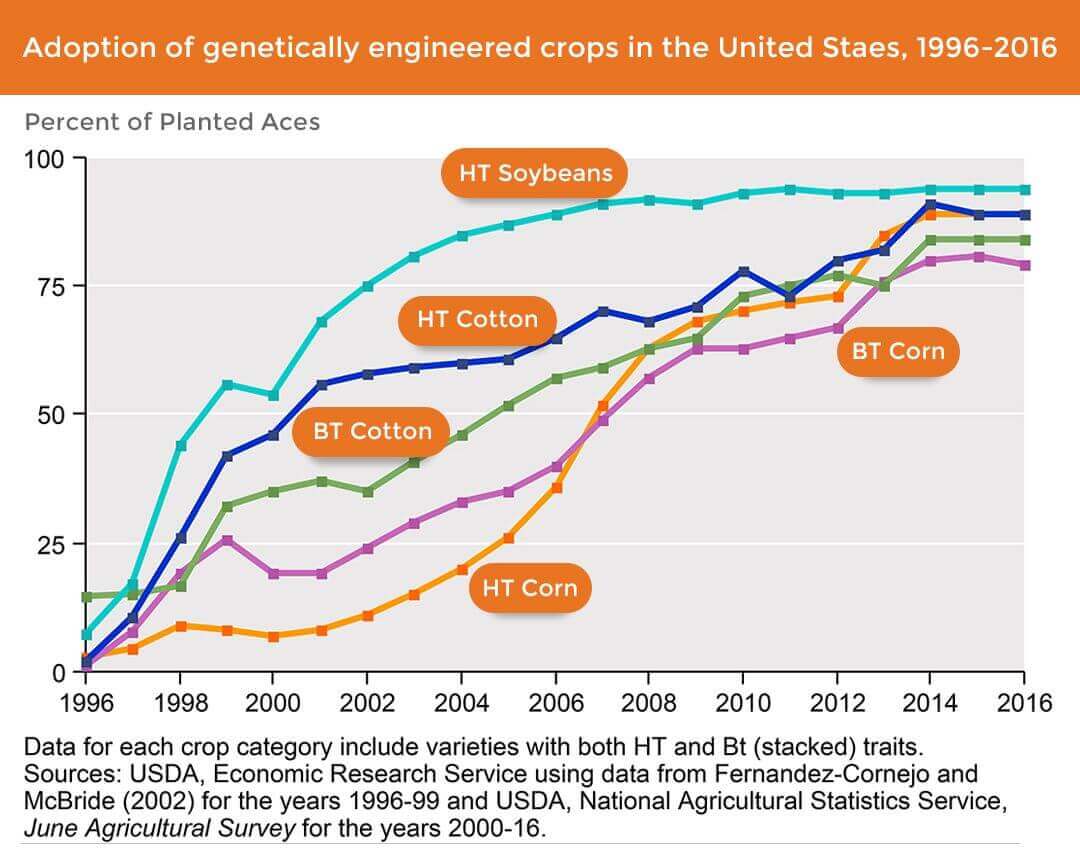

Based on U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) survey data, herbicide-tolerant soybeans went from 17 percent of U.S. soybean acreage in 1997 to 68 percent in 2001 and 94 percent in 2014, 2015, and 2016.

Plantings of herbicide-tolerant cotton expanded from about 10 percent of U.S. acreage in 1997 to 56 percent in 2001, 91 percent in 2014, but declined to 89 percent in 2015 and 2016.

The adoption of herbicide-tolerant corn, which had been slower in previous years, has accelerated, reaching 89 percent of U.S. corn acreage in 2014, 2015, and 2016.

In theory, genetically modified organisms (GMOs) were to be a boon for humanitarian reasons. After all, the world population continues to grow while cropland can be maximized per acre. If only it were that simple …

Plant, distribute without restriction

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulates the safety of food for humans and animals, including foods produced from genetically-engineered plants. The FDA contends that foods from GE plants must meet the same food safety requirements as foods derived from traditionally bred plants. The FDA regulates foods from GE crops in conjunction with the USDA and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

- FDA — enforces the U.S. food safety laws that prohibit unsafe food.

- USDA — safeguards the health, welfare, and value of American agriculture and natural resources.

- EPA — regulates pesticides to ensure that pesticides are safe for human and animal consumption and won’t harm the environment.

GE crops are regulated according to their intended use, with some being regulated under more than one agency. All government regulatory agencies have a responsibility to ensure that the implementation of regulatory decisions, including approval of field tests and eventual deregulation of approved biotech crops, does not adversely impact human health or the environment. The regulations also provide for a petition process for the determination of non-regulated status. Once a determination of non-regulated status has been made, the organism (and its offspring) no longer require review by the USDA's Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service for movement or release in the U.S.

To produce crops commercially, biotech companies apply for “deregulated status” — a green light from the USDA to plant and distribute without restriction. Among the leading deregulated GE crops:

Genetically modified soybeans are the second largest U.S. crop after corn. GM soy is used primarily in animal feed and in soybean oil, widely used for processed foods and in restaurant chains. It's also used to make an emulsifier (soy lecithin), which is present in a lot of processed foods, including dark chocolate bars and candy. Herbicide-tolerant soybeans account for 94 percent of U.S. soybean acreage in 2016. (Soybeans do not have Bt varieties, only herbicide-tolerant.)

Genetically modified cotton is turned into cottonseed oil, used for frying in restaurants, and in packaged foods (potato chips, margarine, and cans of smoked oysters). Some parts of the plant are used in animal feed, and what's left over can be used to create food fillers, such as cellulose. Herbicide-tolerant cotton accounts for 89 percent of U.S. cotton acreage in 2016. All GE cotton — acreage with either or both HT and Bt traits — reached 93 percent of cotton acreage in 2016.

Genetically-modified corn is in many different products, including the ingredients used in processed foods and drinks, including high-fructose corn syrup and corn starch. The bulk of the GM corn grown around the world is used to feed livestock, and some is converted into biofuels. Herbicide-tolerant corn accounts for 89 percent of U.S. corn acreage in 2016. All GE corn — acreage with either or both HT and Bt traits — accounted for 92 percent of corn acreage in 2016.

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma link

Glyphosate is a herbicide, applied to kill both broadleaf plants and grasses. The sodium salt form of glyphosate is used to regulate plant growth and ripen fruit. Glyphosate is present at all levels of the food chain: in water, plants, animals, and even in humans. Every study that has measured human contamination with glyphosate has found it.

Glyphosate is the main ingredient in Monsanto's widely used herbicide Roundup, which is sprayed on crops to control weeds. In a report released in July 2015, the International Agency for Research on Cancer shed new light on the cancer-causing properties of glyphosate. The report, which took an in-depth look at the latest research, concluded that human exposure to glyphosate is linked to double the risk of developing blood cancers, such as non-Hodgkin's lymphoma.

For its part, of course, Monsanto maintains glyphosate has a low risk to human health. The EPA classified the carcinogenicity potential of glyphosate as Category E: “evidence of non-carcinogenicity for humans.” However, that assessment was made in 1991. In the wake of the IARC finding, the EPA is currently assessing glyphosate and the related acid and salt compounds.

Even more troubling is that researchers have found glyphosate residues in food. The IARC noted that a 2007 study found glyphosate residues on six of eight tofu samples made from Brazilian soybeans. In 2014, a study led by scientists from the Arctic University of Norway detected “extreme levels” of Roundup in genetically-engineered soy: “Seven out of the 10 GM-soy samples tested surpassed this ‘extreme level' of glyphosate + AMPA residues, indicating a development towards higher residue levels.”

GMOs permeate the market

“Pest-protected” varieties were among the first genetically-modified crops to be developed, for the purpose of reducing production costs for farmers. Insect-resistant GMOs have been promoted both as a way to kill certain pests and to reduce the application of conventional synthetic insecticides. For more than 50 years, formulations of the toxin-producing bacteria Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) have been applied by spraying in the same way as conventional agricultural insecticides to kill leaf-feeding insects.

In the late 1980s, scientists began to transfer the genes that produce the insect-killing toxinsA poison made by certain bacteria, plants, or animals, including insects. in Bt into crop plants. The intention was to ensure that the toxin was produced by all cells in these GMOs. The Flavr Savr brand of tomatoes was the first GM food product to be introduced in the fresh food market for public consumption. The tomatoes were genetically modified to delay ripening, promising a prolonged shelf-life in the supply chain.

Did You Know

Deregulated GMO foods

The USDA has approved 19 petitions for deregulated status:

Alfalfa … Apple … Beet … Canola … Chicory … Corn … Cotton … Flax … Papaya … Plum … Potato … Rapeseed … Rice … Rose … Soybean … Squash … Sugarbeet … Tobacco … Tomato

Calgene released this brand of GM tomatoes in 1994. Monsanto, which took an initial 49.9 percent stake in Calgene in March 1996 and purchased an additional 6.25 million shares for a 54.6 percent stake in November 1996, acquired the remaining 40.4 share of Calgene for $240 million in 1997.

Today, almost every area in the food production market is using genetic modification: corn, soybeans, sugar beets, peas, potatoes, tomatoes, squash, golden rice, papaya, honey, sugar cane, diary products, meats, salmon, oils, and vitamins.

Grass-roots campaigns in several states are pushing for mandatory labeling of foods with GMOs — something most food companies staunchly oppose. In May 2014, Vermont adopted the first state law requiring companies to label GMO foods, starting in 2016. However, on July 29, 2016, President Obama signed into lawS. 764, also known as the “DARK Act,” which made Vermont's law moot. S. 764 allows companies several ways to disclose the use of GMOs: a QR code, an 800 number, or a website on the packaging — but no further information on the label itself is required.

As The Wall Street Journal noted, the anti-GMO backlash reflects the deep skepticism that has taken root among many U.S. consumers toward the food industry and, in particular, its use of technology. Similar criticism has roiled other food ingredients including artificial sweeteners and finely textured beef, the treated meat product that critics dubbed “pink slime.” The Web and social media have enabled consumer suspicions in such matters to coalesce into powerful movements that are forcing companies to respond.

We are what we eat

When it comes to the foods we eat, consumers are going back to the basics. Nielsen asked respondents to rate health attributes from very important to not important in their purchase decisions. The most desirable attributes are foods that are fresh, natural and minimally processed.

Foods with all natural ingredients and those without GMOs are each considered very important to 43 percent of global respondents — the highest percentages of the 27 attributes included in the study. In addition, about four-in-10 global respondents say the absence of artificial colors (42 percent) and flavors (41 percent) and foods made from vegetables/fruits (40 percent) are very important.

“I’d written about the science and business of genetically-engineered crops for 10 years, and for most of that time, few people seemed to care about them. Then ‘Frankenfoods' exploded onto the front pages …”

Daniel Charles

Author, 'Lords of the Harvest'

Cited as very important by 32 percent of respondents (compared to 26 percent globally), the absence of high fructose corn syrup is tied with GMO-free as the most important attribute for North American respondents (it's No. 21 worldwide).

For most attributes, there is also a gap between the percentage of respondents that say a health attribute is important and the percentage that is willing to pay a premium. For example, 43 percent of global respondents say the absence of GMOs is very important in the foods they purchase, but only 33 percent are very willing to pay a premium for these products — a 10-percentage point difference.

The willingness-to-pay scale in North America is nearly identical to Europe's — 21 percent are very willing to pay a premium, 33 percent are moderately willing and 26 percent are slightly willing, on average. All attributes are weighted similarly in this region. The gap between the attributes that respondents are most willing to pay a premium for (GMO-free and organic products, both at 25 percent) and least willing to pay more for (calcium- and minerals-fortified, both at 17 percent ) is only 6 percentage points.

While health attributes are important factors in purchase decisions for all age groups, percentages are lowest among Silent Generation (aged 65+) respondents. Health attribute ratings are highest among Millennials (21-34), followed by Baby Boomers (50-64), Generation X (35-49) and Generation Z (under 20). The attributes gaining the most favor include products that are GMO-free, have no artificial coloring/flavors and are all natural.

‘Irrational considerations'

Daniel Charles' Lords of the Harvest: Biotech, Big Money, and the Future of Food laid bare the scientific breakthroughs of the early 1980s and the decision by Monsanto to dive headfirst into biotechnology. From the book's prologue:

When I first started working on this book, I thought my most difficult challenge would be to get people interested. I'd written about the science and business of genetically-engineered crops for 10 years, and for most of that time, few people seemed to care about them. Then “Frankenfoods” exploded onto the front pages, and the partisan debate that engulfed them became a blessing and a curse. People started to care about this topic, which I liked. But I sometimes felt as though I'd wandered by accident into no-man's land between two hostile barricades. Each side wanted to pull me to safety behind their particular fortress of ideology, information, and logic. I tried to resist them. It was confusing out there in the middle, but the view was better.

Lords of the Harvest explains Monsanto's quest to re-write the rules of the seed business and how it ended up in a feud with the world's largest seed company, Pioneer Hi-Bred International. It also outlines the forces and the personalities that drove Monsanto toward decisions that transformed the company, in the eyes of many, into a villain with ruthless ambitions that spanned the globe.

“People believe that technologies are driven, more often than they really are, by completely rational considerations, and particularly by the idea of maximizing profits,” said Robert Post, former president of the Society for the History of Technology. “But I am firmly of the view that technologies are driven by irrational considerations.”